On Power, Privilege and Performance: Bono & Jefferson Hack in Conversation

As his new memoir Surrender is published, Jefferson Hack talks to his friend and sometime creative collaborator Bono about politics, near-death experiences, and his “messianic complex”

JH: It really felt like you hacked the political and media systems of America to get George Bush to give $15 billion for Aids emergency relief. That was, for me, a great rock and roll swindle.

B: Somebody called it bum-rushing the government. With Bush it was $15 billion, then the really amazing thing is that Obama followed through with $54 billion over his two terms. He didn’t want it renamed – he allowed this to be Bush’s initiative, which tells you of the kind of man he is. The point is, for all the posturing and the pontification people had to suffer from the likes of me and many others in the UK (like Richard Curtis or Bob Geldof), we got the checks cashed as well as signed.

JH: How do you not end up becoming co-opted by them and not becoming like them? I know you had to spend time with so many people on all different sides of the political fence to achieve the results, but Bob Geldof famously said, “You can’t trust politicians. It doesn’t matter who makes a political speech. It’s all lies – and it applies to any rock star who wants to make a political speech as well.” What would you say to that?

B: Bob is the Miles Davis of conversation. Actually, no, he’s the Jackson Pollock of conversationalism. He’s the most articulate man I’ve ever met – but that line is bollocks and he would know it. The truth is that a lot of politicians work much harder than you think, for a lot less than you imagine and a lot of them are quite honest.

Some of the things I’d be walking into – meeting these lawmakers in the House of Representatives, meeting their chiefs of staff, meeting their families – some of them would have politics that would make my skin crawl, but I saw how hard they worked and that they lived away from their families. I thought, “I’m an extremely spoiled rockstar who’s overpaid for what I do and over-rewarded,” and I had to climb down off my high horse a bit.

We do need artists involved in the body politic and if you go back to the Greek idea of democracy and the Senate, they were poets, they were philosophers and there were scientists in there before it was called science, all feeding into building this civilisation – and in Ireland, that’s not unusual.

JH: You came out of a difficult time in Ireland. Your band was born during the Troubles and you had John Hume and David Trimble onstage together, while you held their hands.

B: I robbed that image from Bob Marley. He, famously in an election, thought the most important thing he could do was to be the interface between these two political rivals, as Jamaica was bursting into flames. U2 grew up 90 or so miles from the border so we had experience with the Troubles, yes, but there were people not far away who were being beaten up really badly by politics and by religion.

JH: I have to ask you about yours and Edge’s trip to Ukraine, because there’s a chapter where you went to meet Zelensky. How would you describe him?

B: He’s an actor, probably a writer, and his right-hand – this guy called Andrii Yermak – is a film producer. They are at their very heart storytellers and our politics is very often hostage to our storytelling. We have to be very careful of simple stories and simple plots. Trump’s appeal was that he spoke in fairytales, Grimms’ fairy tales, largely the monsters at the door, at the border, the monsters under the bed. They were understandable, they were effective communications, whereas a lot of progressives speak in a kind of progressive rock. It’s like you can’t follow the tune, can’t follow the melody line.

It was very helpful to meet with these people who understand that if they don’t get their point of view across to the civilised world, that their civilisation will be over. They are that dependent on our support and so they put a lot of effort into communication with the outside world, including inviting myself and Edge to go there.

“Any good frontman needs a messianic complex, that goes without saying, but a white messiah complex is really dangerous, especially if you’re campaigning for universal access to Aids drugs, or increased aid flows from G7 countries to the poorest countries on the planet” – Bono

JH: I wanted to talk about showmanship and performance, because there’s a whole chapter in the book dedicated to that, where you talk about how hard it is for you to turn yourself off and step out of the song. What is the psychology that’s going on there?

B: There’s very little scholarship, very little writing on the psychology of the performer. There’s definitely more about acting and how actors can negotiate their characters.

JH: Why is it different to inhabit a character?

B: You’re inhabiting a song, you’re inhabiting a feeling. Sometimes it’s harder to shake those feelings off than you’d like to admit.

JH: They’re your emotions, they’re not an inherited emotion.

B: Exactly. You meet performers and they often feel very hollowed out as individuals because they have been. What is the effect of being in front of a crowd of people large or small? Is it a difference if it’s large or small? Can we measure a feeling in a stadium, at a football match?

JH: In that energy transference is bigger, and therefore better?

B: I really don’t know. I wonder if the feeling that you pick up from a bigger crowd is different. In The Showman, I took the line and Gavin Friday said, “If you’re a performer insecurity is your best security,” because performers are people who know when they’re losing a room. If somebody’s taking a piss with the 60,000 people in a stadium at the wrong moment in the song, and that is going to bother you, you know you’re a performer. I wanted to write about that more in the book, that feeling where you expect the ego to be exploded through being famous, when it often implodes [instead].

JH: It was really mind-blowing when you said the things that make you successful in the first half of your life no longer work for you in the second half that they even work against you. What are some of the strengths that you now feel you need to overcome? Is it still a work in progress?

B: I like to think I was very present for my children and we brought them with us around the world when we could, but I had to pinch myself occasionally to notice the moment I was in. For your own spiritual wellbeing you have to stop describing Everest and then climbing it. You might just need to describe the situation you’re in and stay there. Just take it in, because it’s amazing. What I went through at the very start of the book, you’ll understand waking up feels like a really great thing to me [now].

JH: Is that to do with being born with an eccentric heart?

B: Yeah, when you have that sort of shock to the system, you know, I nearly lost my life, so I’m very grateful for those things. I want to spend time noticing them, noticing the stuff around me and noticing the people around me.

JH: I just don’t think there are a lot of role models, or writers, or narratives in art, that show us how we can surrender in victory as we can in defeat. You’re one of the few, then there’s Patti Smith.

B: Yeah, Patti Smith is a real inspiration for me. Watching her physicality, I’ve learned a lot. Watching her standing on a stage, watching her stand inside herself as she spits out those words, some people have the power. It’s a lesson in so much. Edge says to me that I look at my body like it’s an inconvenience and so I’m starting to take my body more seriously now, in terms of looking after it. But also to be on a stage, to be present. I’m really excited about being a performer in a band with my friends and I’m excited that we might be able to make our best album that we hear already in our head. We want to make an album of unreasonable guitars. We want to make this rock and roll album, a really uncontemporary work.

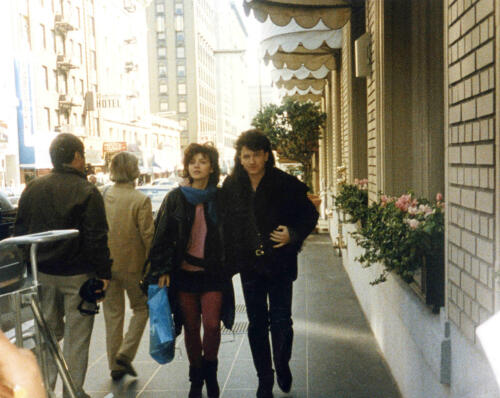

JH: Has [your wife] Ali read the book?

B: She has. There was one piece she wanted to take out because she thought it was too private. She had no problems with it really, except for my spelling.

JH: Your relationship with Ali is the spine of the book. It’s so powerful for anybody to read this book who has absolutely no interest in U2, who just wants to understand how to hold a relationship together because you go through all the highs and lows in the book.

B: It’s funny, she said she winced but she’s not squeamish. She just really didn’t want the portrayal of our relationship as sentimental. I’ve always tried to avoid that in the songwriting and our love songs are quite sort of haunted and hunted. I don’t think relationships are ever just about romance, even when they are, even when you’re in the first flushes, there’s always something else going on. She was amazing, because I’m exposing her too, and it’s not just my life. To be down at the bottom of the sea together, sometimes the water gets really dark when you go down there and you can lose each other. I guess this is a diving analogy? You reach out and you can’t find that hand, it’s a shock to the system, you’re on your own, you go quickly back to the surface. If you go too quickly, there’s the bends, but when you get there another head pops up beside you. It might be further away than you thought and it’s her. You’re gasping a little – I mean, I was great down there – but it’s much better being up here.

JH: There are many pilgrimages in the book – is there an unfulfilled pilgrimage that you’ve always wanted to take?

B: There is an old walk that you can do called the ’Camino [de Santiago]’, which I’d like to do. It sounds like a very old religious pilgrimage. I think I might be coming to that point in my life where ritual and ceremony are more interesting to me now. I see the pandemic of mental health that is around us and I wonder how we’re all going to manage to get through with our modernity. Even though some of the most inspiring people in my life are atheists – Lucy Matthew is at the top of the list – but I have countless people that are way more Christian than I will ever be, and they’re atheists. There are some Zen Buddhist practices that I would like to explore; I think they’d work well with my daily practice.

JH: Your life is an epic movie and I hear there is a U2 film in the works. Can you tell me any more?

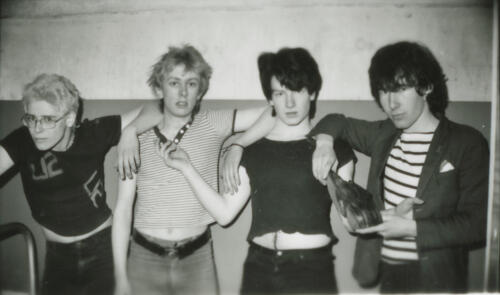

B: It’s a drama series and it’s set in the early days. JJ Abrams of Bad Robot [Productions] rang me up and just said, “Your origin story is extraordinary. Can we look at it and get some writers and some clever people involved?” It isn’t completely set yet by any means, but it’s using the book as a jump-off point. I tried to make this a ’wemoir’ rather than a memoir.

JH: I wanted to ask you about the [Bob] Dylan quote you use at the start; I felt that even though every surrender starts with you, it’s never only about you – you’re also held by the band, by your friends, by your wife, by your family, by God, by all your fans, so it seemed like that quote is more applicable to a solo artist, or a recluse, than to you.

B: I’m about horizontal relationships rather than vertical. I don’t want to have a boss, I don’t want to be a boss. The one vertical in my life is whatever we call God’s love. God is love and if it’s not love, it’s not God. Though you appreciate community and congregation, you’re an audience and you feel the divine around you even in the natural world. There is a part of this surrender that is on your own. And it’s you. And you have to make that moment happen. It’s terrifying to let your hands off the steering wheel. For me, I ended up in the best job in the world with the best people in the world, so it turned out very well for me. For others, it’s brought them to work in Bangladesh right now as their country’s drowning. In that moment of surrender, you will find the most useful version of yourself. For me, that’s maybe the only thing I do on my own.

Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story by Bono is published by Penguin, and is out now.

Lead image is courtesy of Spencer McPherson www.stillmovingmedia.com.